GAVLAK is pleased to present Details of Impossible Past Lovers, a solo exhibition by Judie Bamber. The exhibition features new and recent works that span several decades of the Los Angeles–based artist’s sustained investigation into intimacy, realism, and the politics of looking. Across painting, drawing, and watercolor, Bamber has developed a meticulous and emotionally charged practice that slows the act of viewing, inviting sustained attention to images shaped by desire, memory, and power.

Working from appropriated photographs—ranging from family snapshots to mass-media imagery—Bamber recontextualizes her subjects through fragmentation, cropping, and precise realism. Her work lingers between tenderness and confrontation, reimagining eroticism without objectification and treating realism as a mode of excavation rather than mere representation. As critic Annabel Keenan writes, Bamber’s work “creates a language of intimacy that feels wholly her own,” one that asks viewers to reconsider how images of the body are circulated, mythologized, and consumed.

Born in Detroit in 1961, Bamber entered CalArts in 1979 at a moment when feminist art histories were largely absent from the institution. Working against resistance to her subject matter, she pursued a practice that turned inward rather than distancing itself intellectually. Early works depicting sex toys and closely cropped female anatomy confronted taboos around sexuality with a combination of clinical precision and emotional care—less about shock than revelation.

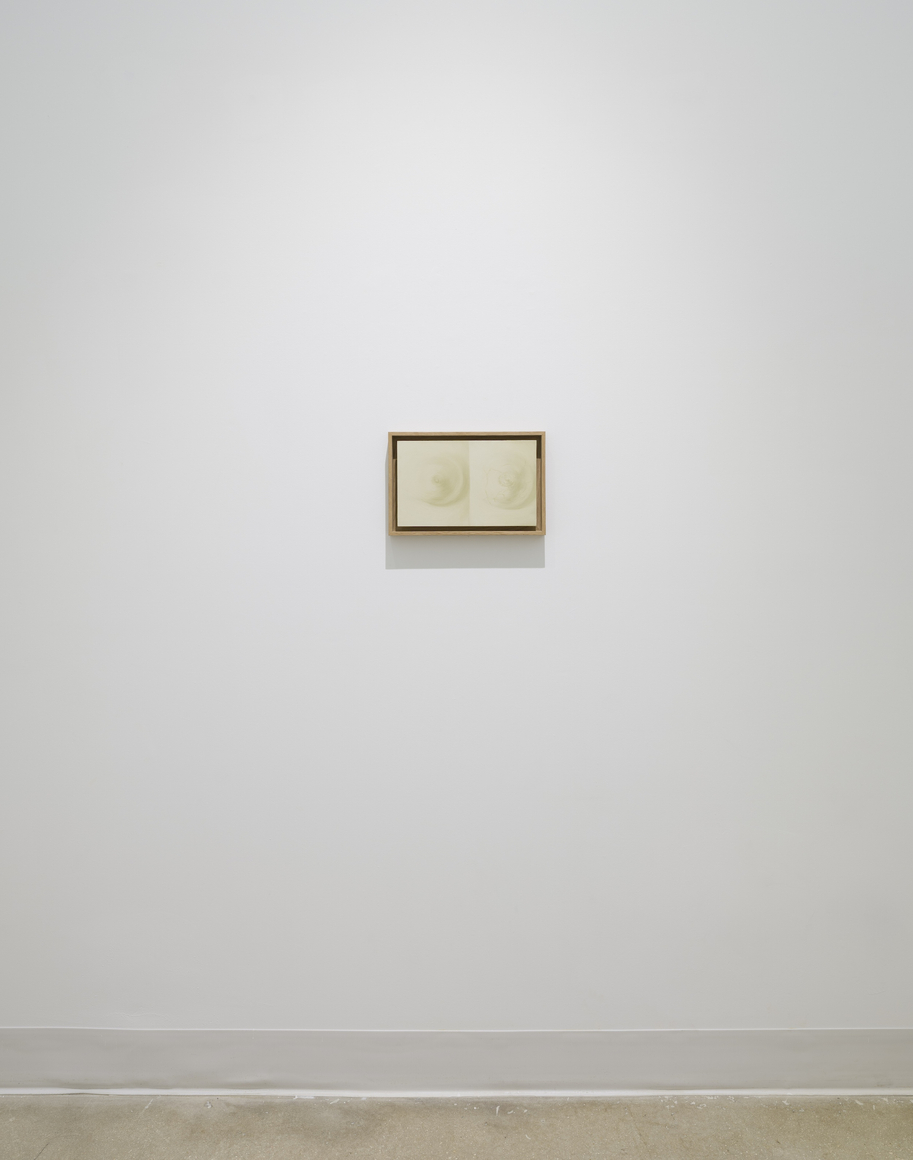

A central thread in Bamber’s practice is her long-running series Are You My Mother?, begun in the early 2000s. Drawing from photographs taken by her father of her mother throughout the 1960s, Bamber approaches the family archive as both portrait and puzzle. Rendered with restraint and emotional acuity, these works transform domestic imagery into meditations on femininity, performance, and inherited desire. As artist and writer Nayland Blake observes, “In Bamber’s paintings, looking, touching, time, and remembrance are in intimate conjunction.”

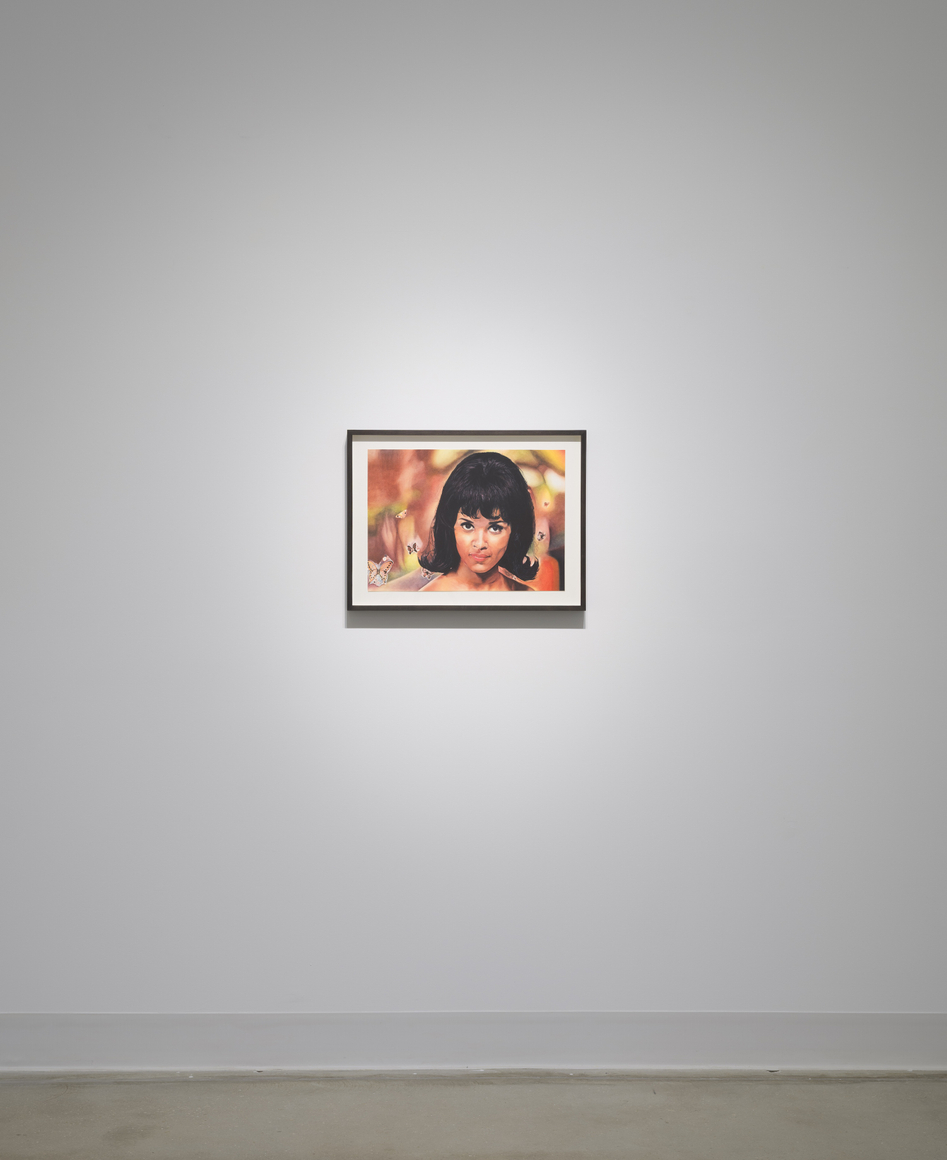

More recent paintings based on 1960s Playboy centerfolds extend Bamber’s inquiry into mass-distributed images of femininity. By isolating fragments and restoring the women’s names, Bamber slows down the centerfold and reframes it as a site of critical intimacy. For Blake, this process is less about representation than transformation: “The image’s power is confronted and worked through by being turned into material,” shifting the photograph from spectacle into a space of ethical and emotional reckoning.

In an era defined by image saturation and accelerated consumption, Bamber’s work insists on slowness, care, and ethical looking. As Blake writes, “Every painting contains two kinds of time coiled within it: the flash of vision and the trail of touch.” This exhibition presents an artist whose practice is defined not by spectacle, but by accumulation—of emotion, technique, and perceptual awareness—inviting viewers to reconsider the emotional and ethical stakes of every image encountered.