“MASHA’ALLAH,” exclaimed my fellow travelers upon learning that I was headed from Jeddah to the holy city of Medina: the Pakistani driver, the jolly Saudi desk agent, my Sudanese seatmate with bloodshot eyes. When I explained, in broken Arabic, that I would continue on to Al ‘Ula, a speck of a town more than a hundred miles away, they were less impressed. In 2017, Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman set up the royal commission of Al ‘Ula (RCU) to develop the backwater’s breathtakingly preserved, UNESCO-anointed carved rock art of the ancient Lihyan and Nabatean kingdoms into a premier tourist destination. Nobody, I was told more than once, wanted to repeat the mistakes of nearby Petra, which is overdeveloped and heaving with touristy schlock.

But they certainly didn’t mind LARPing the 1996 Spice Girls video for “Say You’ll Be There”: high desert, sun reflecting off metallic surfaces, and a cohort of sunburned Westerners dressed like extras from Mad Max. This was Desert X AlUla, the Saudi edition of the Coachella Valley–based sculpture biennial, organized by artistic director Neville Wakefield alongside Saudi curators Aya Alireza and Raneem Farsi. Ed Ruscha protested the union by quitting the board in a move reminiscent of Western institutions consciously uncoupling from KSA funding following the assassination of Jamal Khashoggi—referred to furtively only as “J. K.”

In a police state, you tend to pick up certain bodily tics, especially when you worry you might have said the wrong thing or been overheard by the wrong person. At lunch with writers and curators one day in Jeddah, the collective darting eyes and quick over-the-shoulder scans of the surroundings that ensued when J. K. came up were already familiar to me, coming from Dubai, whose beefed-up surveillance infrastructure lends every interaction, every foray into the public, an anxious burr of watchfulness. It was a rare glitch in the laid-back cosmopolitanism of Jeddah that otherwise felt like a warm arnica salt bath. The city and the culture were so familiar but that tension of being constantly tracked seemed to have dissipated, if you were non-Saudi.

I had arrived two days prior to catch the first day of 21,39 (a latitude-longitude crosshair to remind you it’s Very Site-Specific). Previously known as Jeddah Art Week, the annual event was initiated in 2013 by the Saudi Art Council, a name whose officialdom masks the fact that it’s a private group of local patrons. This seventh edition, titled “I Love You, Urgently” and curated by Maya El Khalil, featured twenty-one artists and took sustainability contra the Anthropocene as its theme. One venue was a newly renovated house in Jeddah’s Al-Balad district, founded in the seventh century but mostly built in the last couple hundred years. Unfortunately, not much was installed (that show would open the next evening), though Maha Nasrallah’s burnt tires and garbage bins—a reference to Beirut’s municipal crisis protests—and Raja’a Khalid’s holographic pottery diffusing a Tesla scent, that new car musk, intrigued. At the SAC headquarters, many raved about Marwah AlMugait’s filmed performance, a lyrical—if opaque—ode to women “in collectivity” (with one another, trees, and the earth). Meanwhile, Farah K. Behbehani offered dual interpretations of a traditional Kuwaiti seafaring song. The lyrics were perforated into an intricately folded, dragon-like paper sculpture, placed on a suspended fabric platform and then rewritten on the ground, in geometric Kufic script, with colorful plastic microbeads. Many artists reprised this formula of Khaleeji heritage meets ecological devastation, none better than Sultan bin Fahad, whose installation incorporated melodic, gulpy camel-herding calls, discarded melted gallon bottles found in the desert, and a camel-hair rug branded with glyphic markings.

The opening party that night was loungy and uneventful—or so I was told. As seemingly everyone in the region’s art scene arrived in Jeddah, I was en route to Al ‘Ula, hurtling through rural deserts in total darkness. Excuse the cliché, but I have never seen stars so bright. A feature of the area, apparently, for the next day, the smooth-talking RCU CEO announced that their shopping list included an observatory, in addition to a nature reserve and resort designed by—who else?—Jean Nouvel. And a fortuitous starry alignment inspired Lita Albuquerque’s future-is-female paean to a fictive astronaut, a work trumpeted as the first figurative public sculpture seen in Saudi Arabia for centuries. Painted International Klein Blue, the thing sits atop a hillock surrounded by large circular IKB-pigmented splotches scattered around the valley, forming a star map of the opening night’s sky.

In contrast to 21,39’s charming pitch-in-and-make-do vibe, Desert X was a slick affair, fascinating in its ghoulish synthesis of corporate pabulum—“Two deserts speaking in one voice,” director Susan Davis enthused—and sweetly earnest Come to Brazil entreaties, and some stunning art. The organizers were keen to remind everybody that the site was the real star, despite such monumental works on view as Rashed Al Shashai’s plastic pallet pyramid. “You cannot compete with the landscape that surrounds you here today,” Farsi said in the press conference. She was echoed by Wakefield, who offered that “this is not a curated show. . . . It’s actually curated by the landscape.”

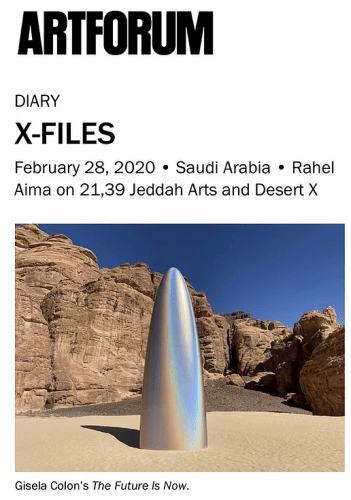

Gisela Colon, The Future Is Now.

But truly, how could art compete with the site, a vale so magical that it seemed to imbue those primordial pigments of sienna, ocher, and umber with new life? The other commissions didn’t try, and as such were all the better for it. Highlights included El Seed’s unusually subdued Emirates-beige calligraffiti sculpture of swooping 3-D Arabic letterforms; Zahrah Al Ghamdi’s serpentine river of variegated date tins, sublimely cast in the golden hour; and works from Rayyane Tabet and Muhannad Shono that gestured toward the flow of oil with, respectively, a spare steel-ringed pipeline and gushing black cables. Gisela Colon’s silver-bullet-like obelisk—curvy and iridescent on one side and, where the sun couldn’t shine, flatter and gray—represented the rare perfect fusion of art and setting. She explained that the carbon-steel composition referred to the Californian aerospace industry. As I waited for the madding crowds to deplane—21,39 had chartered a jet to shuttle the VIPs, clout presumably more urgent than environmental degradation—it was hard not to think about who sells and buys these jets, bombs, and bullets, about the American and Arabian deserts that speak in one voice and sing a familiar song.

— Rahel Aima