Transport yourself, if you will, back to 2004, the heady era when Von Dutch trucker hats paired with aviator sunglasses were the celebrity uniform du jour, Kim Kardashian was still Paris Hilton’s closet organizer, and Lauren Conrad was merely a student at Laguna Beach High School and not yet “the girl who didn’t go to Paris.” It was also an election year, and warmongering buffoon George W. Bush emerged victorious against the lustrous-locked democrat John Kerry to serve a second term. Galvanized by the prospect of another four years of foreign war and government-sanctioned torture, Los Angeles-based artist Lisa Ann Auerbach began to knit, cranking out a series of sloganeering sweaters offering a searing indictment of the Bush administration: the dynamite belt of a suicide bomber rendered in intarsia knit underneath an American flag and text reading, “When there’s nothing left to burn, you’ve got to set yourself on fire.” The strength of Auerbach’s work lies in its juxtaposition, delivering scorched earth messages through a medium best known for its cozy softness than its political activism.

A decade and a half later, in the midst of a global pandemic and facing the reelection of a different presidential embarrassment, Auerbach once again began knitting with renewed purpose, embarking on a series of squares that immediately memorialized current events: Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s lace collar, the dollar amount of Donald Trump’s tax return, even the name of National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases director Dr. Anthony Fauci, rendered in black metal font. GARAGE spoke with Auerbach about the history of political knitting, her creative process and the particular irony of being an artist whose work thrives under politically demented conditions.

"WHEN THERE'S NOTHING LEFT TO BURN, YOU'VE GOT TO SET YOURSELF ON FIRE," 2008, MERINO WOOL. COURTESY OF THE ARTIST AND GAVLAK, LOS ANGELES / PALM BEACH. COLLECTION OF THE HAMMER MUSEUM.

Has anything about your knitting practice shifted over the past decade or do you still approach the work in a similar manner?

A lot of my work is rooted in the idea of self-publishing. I think of the sweaters as making the self public because if you’re out on the bicycle or in the world, you’re making your views public on a sweater. Now with the rise of social media, it’s easier to self publish in a way. When I started making political knitwear in 2004-2005, it was pre-social media—it wasn’t pre-Facebook, I guess, but it was before the deluge. I was doing this project called Knitters for Kerry and it felt like a really lonely pursuit, being the only political knitter out there—or at least the only one I was aware of. It feels like a lot more people are paying attention to issues and putting their political thoughts out there now which on one hand is great, but on the other hand I just feel like I’m lost in an ocean of everybody’s outrage.

I’ve taken off six months here, a year there, but I keep coming back to knitting as one of the central ways I make work. It just feels like a natural venue for the kinds of things I want to express. I like the uniqueness of how messages look knit as opposed to drawn or computer generated. They have a real texture and a warmth to them that’s missing in other modes of expression.

"NEVER FORGET (KNOCK KNOCK)," 2007, MERINO WOOL. COURTESY OF THE ARTIST AND GAVLAK, LOS ANGELES / PALM BEACH. PRIVATE COLLECTION.

The sweaters you made in the mid-2000s were all so intricate and complex, combining messages and patterns, whereas the squares you’re creating now feel more unfiltered and immediate. Do you feel the need to broadcast more quickly because of social media?

That’s part of it. I decided that for October I [would] to try to make one square a day as a challenge to get me back in the studio, making things again, using different yarns that I normally don’t use. I was asked to participate in a fundraiser for the Institute of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles that asked for 12 x 12 inch work and I thought that was the worst size ever. But then I made a 12 x 12 piece and realized, actually this is the best size ever because you can make these sketches, these real quick knits that you don’t have to be too married to.

I’m thinking of them really as experimental for me. I’m trying to say a lot of the same things that are already out there but maybe in different ways; not necessarily replicating everything that’s out there but changing the meaning a little bit through knitting.

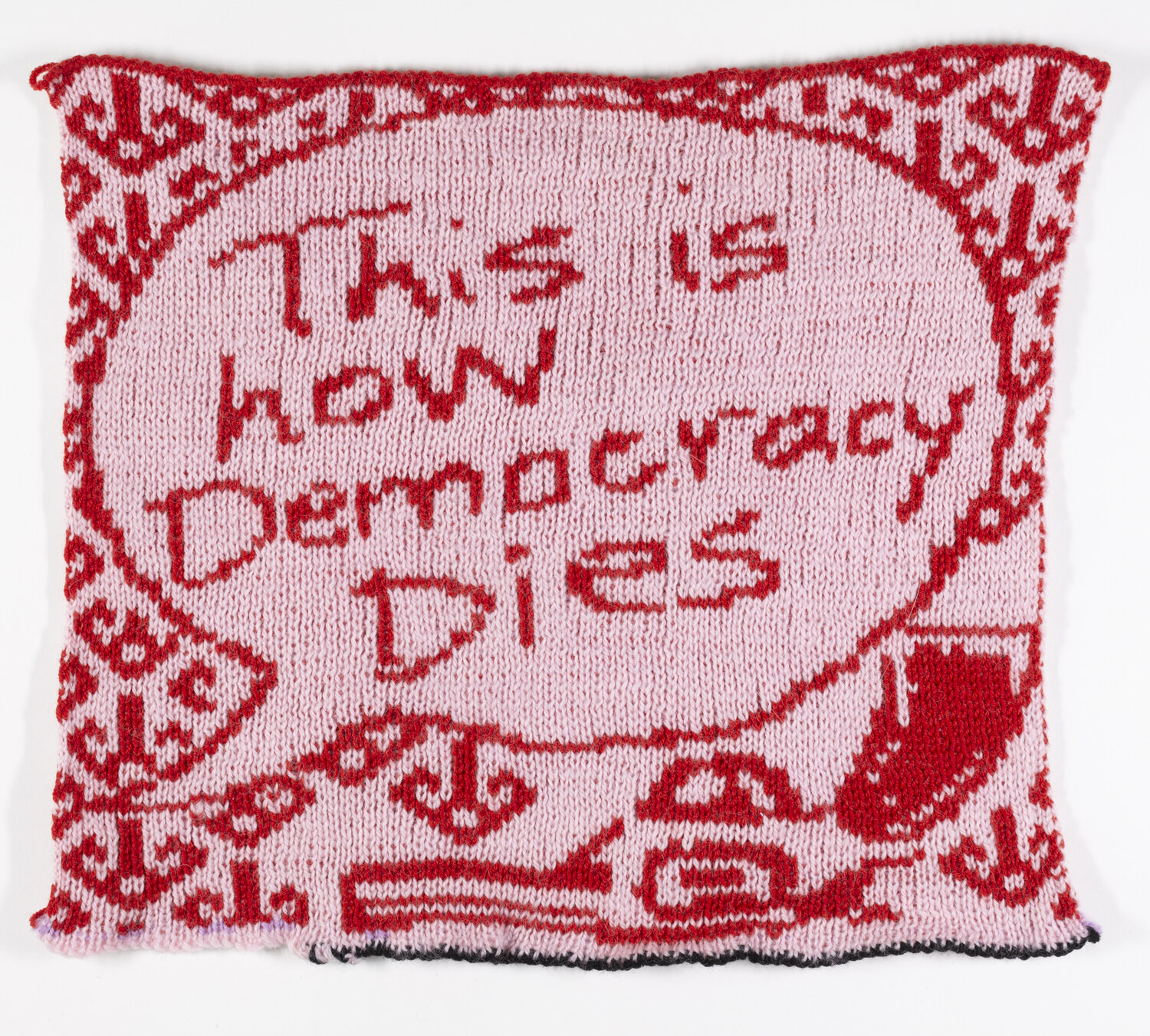

"THIS IS HOW DEMOCRACY DIES," 2020, WOOL. 12 X 12 IN. COURTESY OF THE ARTIST AND GAVLAK, LOS ANGELES / PALM BEACH.

"THIS IS HOW DEMOCRACY DIES," 2020, WOOL. 12 X 12 IN. COURTESY OF THE ARTIST AND GAVLAK, LOS ANGELES / PALM BEACH.After you’re finished creating a square do you feel like you’ve expunged something?

You mean like from my deep psyche?

Yes.

I don’t always think of my work that way. Sometimes I just want to see them made.

So the purpose of them isn’t cathartic?

A personal exorcism? No. I think I’m just sort of joining the din on social media. But right now I’m standing in my studio looking at the ones I’ve made and it just looks like this process of moving through time and ideas. They’ve become a document of this time.

"FLY," 2020, WOOL. 12 X 12 IN. COURTESY OF THE ARTIST AND GAVLAK, LOS ANGELES / PALM BEACH.

Is it difficult being an artist who creates really potent work under traumatic circumstances? I can’t imagine that’s an easy way to go about life.

I guess I didn’t make a lot of overtly political work during the Obama years, huh? The day after Trump was elected in 2016, which seems like a lifetime ago, I started doing these slogans that were gouache on paper and selling them as a fundraiser. I put it on Instagram and said if anyone gives $500 to an organization that goes against the Trump administration they can have a painting. I thought I would do two or three of these but I ended up doing over 200 over the last four years. I guess this particular kind of work thrives during negative political situations but honestly there’s always something to be upset about.

Do you think you will continue on with the squares post-election or will you shift towards something else?

I’m honestly not that organized in terms of strategy. I never think, “I’m going to be doing this,” or “I have this goal.” I’m just kind of reacting in a way. Right now I’m hand-knitting some Hønsestrik sweaters. “Hønsestrik” is a Danish word that means “hen’s knitting” or “chicken knitting.” Women would knit political or ideological iconography into these sweaters and it really took off in Denmark in the 1970s. Somebody told me about it when I was visiting Norway in 2010 and I was like, “Oh my god! These are like my spiritual forebears.” It's a super interesting chapter of knitting history that’s pretty much unknown in the West so that’s something I want to expand on in the future.